This month we are going to discuss Creating Compelling Characters that drive the plot and keep readers coming back for more.

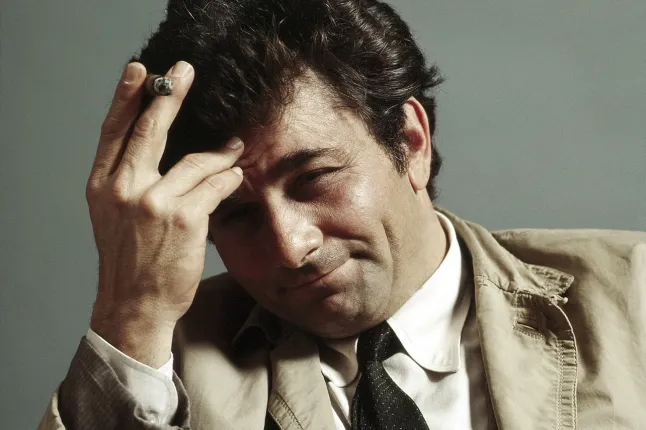

For your Protagonist: The saying “Bigger than Life” holds true – the more memorable the character, the more likely your reader will be eagerly awaiting your next release, or checking out your backlist. A few of my favorites from television would be Kensi Blye from NCIS  LA, or Hondo from SWAT, or even going back a few years, Columbo played by Peter Falk. While Hondo and Kensi are modern day - physically above the norm and more than capable, Columbo always came across as bumbling, but persistent. He just kept coming back to pester the perp until he finally had proof his hunch was right without all the physical capacity that we see in today’s TV law and suspense heroes and heroines. Another of the memorable heroes of today, first in literature and then in a TV series, was James Alexander Malcolm McKensi Frasier – AKA Jamie in Outlander. And everyone who has ever watched NCIS and misses her, there’s Abby Sciuto. The lab genius who can tell you where someone has been by the grass found in a boot tread in the dirt, or the make of the getaway car from shards of broken fender and just about anything else the team needed to get their man.

LA, or Hondo from SWAT, or even going back a few years, Columbo played by Peter Falk. While Hondo and Kensi are modern day - physically above the norm and more than capable, Columbo always came across as bumbling, but persistent. He just kept coming back to pester the perp until he finally had proof his hunch was right without all the physical capacity that we see in today’s TV law and suspense heroes and heroines. Another of the memorable heroes of today, first in literature and then in a TV series, was James Alexander Malcolm McKensi Frasier – AKA Jamie in Outlander. And everyone who has ever watched NCIS and misses her, there’s Abby Sciuto. The lab genius who can tell you where someone has been by the grass found in a boot tread in the dirt, or the make of the getaway car from shards of broken fender and just about anything else the team needed to get their man.

XX

But what makes these characters so memorable and why did readers fall in love with them?

XX

Kensi Blye comes from a Marine Corps family. She’s fluent in Portuguese, French, Spanish, Japanese and can read lips and Morse Code. She can track with the best of them, outshoot most and is an ace sniper. She can fix a car engine, play poker, wire a house and anything else a father might teach his son. Definitely BIGGER than life. In the words of the woman who played her in the series: “Kensi is a flawed human being like anyone is, and she grows from her mistakes. She’s intelligent. She’s fiercely independent, but after all these years, I think she’s grown to understand that it’s okay to emotionally depend on someone else. Her own traumas of losing her dad, not having a present mom, running away from home as a teenager, living on the street for a while, gave her a sense of no one’s going to give anything to you. You’ve got to go for it yourself and depend on yourself.” In other words, Kensi is a complete character with weaknesses, flaws, strengths, and talents. Not perfect, but definitely unforgettable.

Kensi Blye comes from a Marine Corps family. She’s fluent in Portuguese, French, Spanish, Japanese and can read lips and Morse Code. She can track with the best of them, outshoot most and is an ace sniper. She can fix a car engine, play poker, wire a house and anything else a father might teach his son. Definitely BIGGER than life. In the words of the woman who played her in the series: “Kensi is a flawed human being like anyone is, and she grows from her mistakes. She’s intelligent. She’s fiercely independent, but after all these years, I think she’s grown to understand that it’s okay to emotionally depend on someone else. Her own traumas of losing her dad, not having a present mom, running away from home as a teenager, living on the street for a while, gave her a sense of no one’s going to give anything to you. You’ve got to go for it yourself and depend on yourself.” In other words, Kensi is a complete character with weaknesses, flaws, strengths, and talents. Not perfect, but definitely unforgettable.

XX

For those of you who haven’t watched SWAT: Hondo, the leader of the SWAT team, is a capable leader coupled with an ability to connect with his team members on a personal level. But it’s his own struggles that make him relatable and complex. His character is tested through difficult situations, including dealing with racism. He has a softer side he rarely lets people see – he’s intuitive and concerned about other people’s feelings. He has a inflexible sense of right and wrong and he is a “protector.” He’s the kind of guy we all wish we had watching our back, or just tossing back a beer.

For those of you who haven’t watched SWAT: Hondo, the leader of the SWAT team, is a capable leader coupled with an ability to connect with his team members on a personal level. But it’s his own struggles that make him relatable and complex. His character is tested through difficult situations, including dealing with racism. He has a softer side he rarely lets people see – he’s intuitive and concerned about other people’s feelings. He has a inflexible sense of right and wrong and he is a “protector.” He’s the kind of guy we all wish we had watching our back, or just tossing back a beer.

XX

Jamie Frasier first captured the hearts of readers more than 30 years ago, then TV goers with the character as portrayed by Sam Heughan. To start with, everyone seems to admire a man who wears a kilt and is a dynamic fighter with the broadsword. But Jamie was also scarred and stubborn. So, not the perfect man. He’d been held captive by the British and beaten more than once, so his escape and crusade to keep the spirit of Scotland alive was compelling. As a man, he was fierce, loyal, loving and as mentioned, stubborn.

Jamie Frasier first captured the hearts of readers more than 30 years ago, then TV goers with the character as portrayed by Sam Heughan. To start with, everyone seems to admire a man who wears a kilt and is a dynamic fighter with the broadsword. But Jamie was also scarred and stubborn. So, not the perfect man. He’d been held captive by the British and beaten more than once, so his escape and crusade to keep the spirit of Scotland alive was compelling. As a man, he was fierce, loyal, loving and as mentioned, stubborn.

XX

Then there are the heroes who arise out of a whole different focus. Lee Child deliberately chose to make Jack Reacher a loner and very different from the prevailing view of what makes a hero. He has his own set of rules about justice that often result in violence. But never against the innocent. Child chose to make Reacher a quirky hero – an Army veteran who loves to get on a bus and see where it’s going. Reacher is an introvert with no family, no home, no love-life. The fact that he always runs into a situation where those less capable of righting wrongs or even defending themselves is where he comes to life, and claims his place in reader’s memories.

XX

Now, for my advice on how to make your characters as memorable as these folk: Before you even start to put your character together, I suggest you re-read your very favorite book, or re-watch your favorite TV series, or movie. Pay close attention to WHY you love this character. Take notes and write down the things you found compelling and you’ll probably notice pretty quickly that it’s not the physical appearance that endears you the most. It’s a whole lot of things, big and small that make a character memorable. Give your characters a motivation the reader can relate to and want to cheer them on. Give your made up people traits that make them heroic, but also traits that keep them from being perfect. They don’t have to be handsome or beautiful, shapely or fit. In fact, being less so helps the reader relate and can also give the character a complex about their lack of looks or fitness. Remember Columbo with his bumbling interruptions, his perpetual trench coat, a dog that never behaves and a wife who always loves something that the perp might approve of. But under all that, he’s smarter than he takes credit for, sees things others miss, and always gets his man (or woman.)

Now, for my advice on how to make your characters as memorable as these folk: Before you even start to put your character together, I suggest you re-read your very favorite book, or re-watch your favorite TV series, or movie. Pay close attention to WHY you love this character. Take notes and write down the things you found compelling and you’ll probably notice pretty quickly that it’s not the physical appearance that endears you the most. It’s a whole lot of things, big and small that make a character memorable. Give your characters a motivation the reader can relate to and want to cheer them on. Give your made up people traits that make them heroic, but also traits that keep them from being perfect. They don’t have to be handsome or beautiful, shapely or fit. In fact, being less so helps the reader relate and can also give the character a complex about their lack of looks or fitness. Remember Columbo with his bumbling interruptions, his perpetual trench coat, a dog that never behaves and a wife who always loves something that the perp might approve of. But under all that, he’s smarter than he takes credit for, sees things others miss, and always gets his man (or woman.)

XX

Now for the rest of your characters. Understand the difference between the villain and the antagonist. A villain is always an antagonist and the words that best describe him or her are evil, destroyer, killer, unpredictable, sociopathic, narcissistic and use fear to get their way. An antagonist is someone who stands in the hero or heroine’s way but isn’t necessarily evil. To let your reader connect with either of these characters, the reader needs to see the reasons for their behavior: revenge, hate, greed, sex, drugs, or loss of power. They might also be motivated by a need to be liked, desire not to be alone, a need for attention or religious zeal. Don’t forget the success of the BOND villains who are rich, powerful, also larger than life, enjoy the crime and are egocentric.

Now for the rest of your characters. Understand the difference between the villain and the antagonist. A villain is always an antagonist and the words that best describe him or her are evil, destroyer, killer, unpredictable, sociopathic, narcissistic and use fear to get their way. An antagonist is someone who stands in the hero or heroine’s way but isn’t necessarily evil. To let your reader connect with either of these characters, the reader needs to see the reasons for their behavior: revenge, hate, greed, sex, drugs, or loss of power. They might also be motivated by a need to be liked, desire not to be alone, a need for attention or religious zeal. Don’t forget the success of the BOND villains who are rich, powerful, also larger than life, enjoy the crime and are egocentric.

XX

Finally, there is the rest of your cast. Give all the important support characters the same attention to detail as you give your protagonist, even if their backstory is far shorter and their action here less important. Make sure they have their own goals, motivations and conflict, which just might be part of the conflict with the main characters. There will always be part time players and if they, like the waitress who delivers the meal, or the bank teller who pushes the alarm, have no other place in the story, don’t even give them a name. Unless they will appear later and have an important role to play, just their place in the story is all that’s needed to identify them.

XX

With twelve books published, it’s hard for me to pick out just one or two characters I liked best. But the one I will admit took up a place in my heart long before I even wrote his story, is Matt Steele from THE CANDIDATE. “The photo caught Matt Steele off guard, jerking him back to a time he’d done everything to forget, to emotions he never wanted to relive. In the midst of a hotly contested race for the White House, the photo and the man who brought it to him will challenge everything Matt thought he knew about himself. The choice he faces to put honor on the line could change the outcome of the election and the fate of a nation.” My character is both an honorable and a flawed character. And it’s that very past that’s come back to haunt him that makes him memorable. Matt Steele came to life out of my own coming of age during the Vietnam War. Steele was partly molded and troubled by the things my brother shared with me, the things Scotty had lived through both in war and back home. But like my brother, Steele had come to terms with his past and created a happy and successful life. Until that photograph showed up and pulled him back into the past.

With twelve books published, it’s hard for me to pick out just one or two characters I liked best. But the one I will admit took up a place in my heart long before I even wrote his story, is Matt Steele from THE CANDIDATE. “The photo caught Matt Steele off guard, jerking him back to a time he’d done everything to forget, to emotions he never wanted to relive. In the midst of a hotly contested race for the White House, the photo and the man who brought it to him will challenge everything Matt thought he knew about himself. The choice he faces to put honor on the line could change the outcome of the election and the fate of a nation.” My character is both an honorable and a flawed character. And it’s that very past that’s come back to haunt him that makes him memorable. Matt Steele came to life out of my own coming of age during the Vietnam War. Steele was partly molded and troubled by the things my brother shared with me, the things Scotty had lived through both in war and back home. But like my brother, Steele had come to terms with his past and created a happy and successful life. Until that photograph showed up and pulled him back into the past.

XX

Here are a few of the character references on my shelf that I refer to often:

Here are a few of the character references on my shelf that I refer to often:

The Writer’s Guide series:

The Emotional Wound Thesaurus

The Positive Trait Thesaurus

The Negative Trait Thesaurus

Careers for Your Characters

Character Traits

Building Believable Characters – by Marc McCutcheon - Writer’s Digest

Characters Emotion and Viewpoint - by Nancy Cress

Creating Character Arcs – by K.M. Weiland

The Birth Order Book by Dr. Kevin Leman

(Surprisingly, birth order can often add another layer to your character as there are traits first borns, or onlys develop that second or thirds don’t. Middle kids are often peace makers and the baby of the family, often spoiled by both parents and siblings have another whole view of the world.)

XX

Now that you’ve had a peek at both my methods and some of my favorite characters, hop on over to see what my fellow Blog Hop posters have to say about compelling characters:

XX

Sally Odgers

Bob Rich